The Turkish Competition Authority’s (“TCA”) decision on its recent banking investigation concerning syndicated loans was one of the megahit decisions of the past year. The TCA made precedent-setting evaluations in relation to leniency applications; by evaluating the application within scope of information exchange for the first time in its history and rendering telephone conversations submitted in form of writing with the leniency application as admissible evidence. We previously published an article discussing the ins and outs of the case as well as an article on the liberal approach adopted by the TCA towards acceptance of the leniency application within scope of an information exchange matter.

The final say concerning admissibility of telephone conversations is yet to be declared. However, in the meantime, some insight on evaluation of telephone conversations submitted in form of writing as evidence under both Turkish criminal law and constitutional law may be useful for companies.

The final say concerning admissibility of telephone conversations is yet to be declared. However, in the meantime, some insight on evaluation of telephone conversations submitted in form of writing as evidence under both Turkish criminal law and constitutional law may be useful for companies.

Before further digging into the criminal law and constitutional law analysis concerning admissibility of recording of telephone conversations, let us first explain the background story beginning with the leniency application.

The background story goes like this…

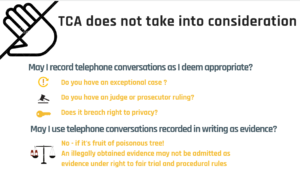

The TCA launched an investigation against 13 banks upon a leniency application. The leniency application included telephone conversations documented in writing between employees of the leniency applicant and the employees of other banks. The relevant documents concerned discussions made over the desk phones of the relevant employees and discussions were recorded by the leniency applicant bank without a judge or a prosecutor ruling. The TCA regarded such recordings as evidence. Whether spoken words may be rendered as admissible evidence for purpose of such investigation was not dealt in detail based on principles of criminal and constitutional law.

Why does it matter?

Overall, competition infringements foresee an administrative sanction and thus, such infringements must not be regarded as an offence/crime but a misconduct/misdemeanor. Where the Competition Act does not provide a clear provision or stays silent in relation to certain points of discussion, the Misdemeanors Act, which provides general provisions, as well as general principles of criminal and constitutional law are rendered binding and thus, such provisions must be applied. This approach is also available in the ECtHR decisions where competition investigations are considered to be subject to rules of criminal procedure law within scope of right to fair trial. Indeed, such application is ratified in various TCA decisions.

With regards to admissibility of evidence, neither the Competition Act nor the Misdemeanors Act provides a special provision in relation to admissibility of evidence. Yet, as per Article 38 of the Constitution, “findings obtained through illegal methods shall not be considered evidence”. Indeed, when the wording in the Constitution is read carefully, it is seen that such findings are not even regarded as “evidence” within scope of constitutional principles. Moreover, matters concerning admissibility of evidence are evaluated under the Constitutional right to fair trial. Indeed, a similar analysis is also available in Article 31 of the Administrative Procedures Act which makes reference to the Civil Procedure Act, where it is stated that illegally obtained evidence may not be used as proof. Such understanding corresponds with the principle of fruit of the poisonous tree under criminal law, which regards illegally obtained evidence as poison and objects use of such findings as proof. Accordingly, admissibility of evidence comes forth as a matter that must be analyzed in light of both criminal and constitutional law principles as well as administrative law principles where a contradiction arises.

However, going back to our case, the TCA does not consider such principles in its analysis despite the contradiction in relation to legality of recording telephone conversations in the first place. Moreover, the TCA takes a further step by using such conversation recordings, which have been submitted by the leniency applicant in writing, as evidence within scope of the relevant investigation.

But what did the TCA say?

In its analysis, the TCA simply noted that authorization provided to the Authority by the Competition Act extended to use of such evidences. The Board evaluated that recording of the telephone conversations is a common/general practice in the banking industry. Based on this consensus, the relevant bank employees were considered to grant consent to recording and use of their communication. Accordingly, the TCA did not further tackle whether an express and specific consent was provided for recordings. For example, it did not investigate whether the relevant correspondences included call recording warnings at the time of the communication. Moreover, a judge or a prosecutor ruling was not sought for recording of the relevant correspondences. All in all, despite the defenses of the parties, the Board noted that use of telephone conversations was lawful for the purpose of the investigation and concluded a competition law infringement via exchange of information based on communications that took place between bank employees, inter alia, over the phone.

And what is the stance adopted by the criminal and constitutional principles in relation to recording and use of telephone conversations as evidence?

Overall, Turkish criminal law enforcement adopts a rather strict approach towards determining, hearing and recording of audio correspondences. Indeed, recording of telecommunications is allowed on strictly regulated exceptional cases and require a judge or a prosecutor ruling. Moreover, use of such correspondences is also very restricted. This is because correspondences are closely linked with freedom of communication, which is enshrined under right to privacy – a fundamental human right protected by the Constitution. Indeed, criminal law also regards infringement of privacy of communication as an offence. Accordingly, the way such telephone conversations are obtained and used plays a significant role for purpose of analysis.

Overall, Turkish criminal law enforcement adopts a rather strict approach towards determining, hearing and recording of audio correspondences. Indeed, recording of telecommunications is allowed on strictly regulated exceptional cases and require a judge or a prosecutor ruling. Moreover, use of such correspondences is also very restricted. This is because correspondences are closely linked with freedom of communication, which is enshrined under right to privacy – a fundamental human right protected by the Constitution. Indeed, criminal law also regards infringement of privacy of communication as an offence. Accordingly, the way such telephone conversations are obtained and used plays a significant role for purpose of analysis.

As previously noted, illegally obtained evidence is regarded inadmissible before the court. In the criminal word, such illegally obtained evidence is considered under the exclusionary rule and the evidence is rendered to be “fruit of the poisonous tree”. In this sense, such findings are rendered inadmissible evidence/proofs, as they would be poisoned and poison the course of the investigation. On this note, it must be reminded that the administrative law enforcement supports such evaluation and follows a similar pattern. Moreover, it must be highlighted that recording and use of such telephone conversations may also be regarded to restrict fundamental human rights as such communications are protected under right to privacy

However, it appears that the TCA does not analyze in detail the nature and means of collation of the telephone conversations. In this regard, bearing in mind that criminal and constitutional law rules and principles serve as overriding principles and are applicable to competition law enforcement, whether use of such recordings is legally admissible remains to be answered